That's how it was...Exhibition: Ingenuity at the service of power. Leonardo da Vinci's codices at the Austrian court

From February 16 to May 16, 2021. Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando.

Exhibition organized by the General Directorate of Cultural Heritage of the Community of Madrid in collaboration with the National Library of Spain, National Heritage and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando,

Ingenuity at the service of power tells a fascinating and little-known story: the presence in Spain between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries of most of the manuscripts written by Leonardo da Vinci. Not only the two Madrid Codexes, which today are one of the treasures of the National Library of Spain, but almost all of those that are preserved distributed in the best museums in the world, in addition to the approximately twenty that disappeared.

Based on this common thread, the exhibition vindicates the importance of science and the transmission of knowledge in the Spain of the Habsburgs, and presents a Madrid that was a fundamental focus of knowledge of the time.

The scientific discourse has been made by a curatorial team formed by Daniel Crespo Delgado, Mariano Esteban Piñeiro, Nicolás García Tapia, Carlos Jiménez Muñoz, Almudena Pérez de Tudela Gabaldón and Elisa Ruiz García, and coordinated by Magoga Piñas Azpitarte, with the collaboration by Almudena Palancar Barroso

Madrid, center of a knowledge transfer network. Science and Technology at the service of power

The establishment by Felipe II of the court in Madrid determined that the Alcázar Real, residence of the monarch and seat of the Royal Councils, became the nerve center of the monarchy. Ambitious projects carried out by mathematicians, cosmographers, astronomers, engineers, architects, doctors, botanists, assayers, artists, watchmakers, were thought of in its dependencies, and from there they were directed. All worked at the service of the monarchs as experts in some of the subjects that made up "imperial science and technique", an essential tool for the exploitation and administration of the extensive territories of the Crown and to show, defend and extend their power.

The Madrid region, both the capital and Alcalá, Aranjuez or El Escorial, the vast territory where the court settled, became one of the most active scientific-technical centers in Europe. Spanish scientists and technicians contributed to this, but also Neapolitans and Milanese, Flemish, Portuguese, Germans and even some English and French. With these engineers traveled proposals and inventions, books and ideas that were shared beyond political borders.

The manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci in Madrid

Its iconic language

The preserved manuscripts of the Florentine artist show an overwhelming creativity and an admirable capacity to express himself through images. His mind was ahead of its time. The encyclopedism of his knowledge prevented him from solving many of the issues conceived. His works are characterized by being unfinished, but everything he did as an author in different fields has been a source of decisive inspiration for generations to come.

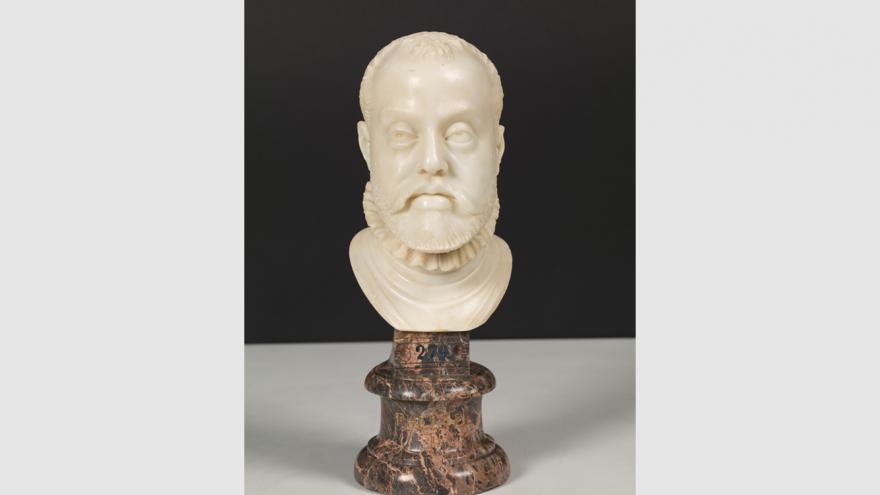

For these reasons, from the middle of the XNUMXth century, intellectuals and artists wanted to own some of his written works. One of them was the sculptor Pompeo Leoni, who brought some magnificent examples of the master to Madrid.

Reading footprints

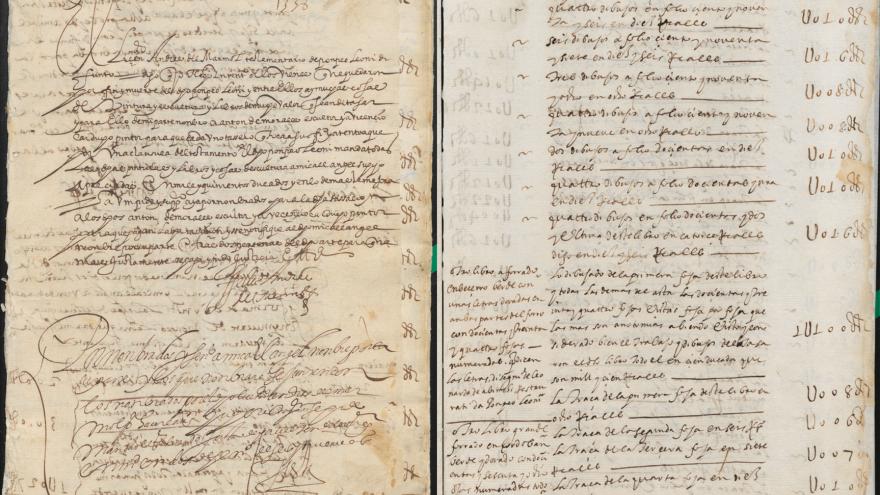

Some original works by Leonardo show annotations made by scholars while reading them. This practice was common at the time. The existence of these notes allows to know the degree of reception of the ideas and the findings of the teacher and shows the circulation and interest in such works.

In some high-quality copies that were part of Pompeo Leoni's heritage legacy, and that remained in Madrid at least until 1613, there are brief comments made by different hands in Spanish and Italian. These are the manuscripts called Windsor Collection, Manuscript B and the Codice sul Volo degli Uccelli. On the other hand, the so-called Madrid I and II Codices, of exceptional value and currently kept in the National Library, lack apostilles. This fact allows us to suppose that its possible owner, the musicologist Juan de Espina, did not facilitate the consultation of these pieces, which were once admired by the Italian painter Vicente Carducho.

The connection with Milan. The architects of El Escorial: Pompeo Leoni, Juan de Herrera, Jacopo da Trezzo

The construction of the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial was the greatest artistic undertaking of Felipe II for which he spared no effort. Its architect, Juan de Herrera, devised machines and more rational work systems to finish the work in an unusually short time for the time. Later, the king focused on its ornamentation, in which teams of Genoese and Milanese were of great importance, apart from allocating the most select pieces from his artistic collections to the monastery.

A neuralgic point was the presbytery of the basilica, with the large polychrome jasper altarpiece centered on the monumental custody of Jacopo da Trezzo. To carve it, Trezzo built mills, such as a mill to carve the hard stone, and used novel polishing techniques. The decoration was completed with the gilt bronze sculptures made in Milan by the Leoni. Pompeo Leoni also acted as the king's artistic agent and was able to obtain Leonardo's manuscripts for him. In that case, they would have had a place in the monastery library, conceived as a great center of knowledge of the time.

Water for life. Civil and hydraulic engineering

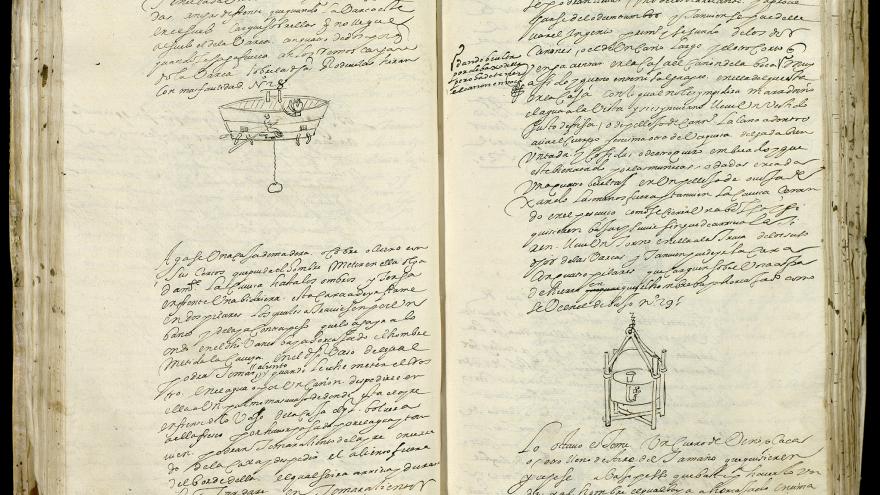

Leonardo da Vinci wrote that water was a substantial part of the Earth and of the human being. His codices are full of notes and drawings from his studies on hydraulics. This interest of Leonardo reflects the efforts of the Renaissance to know the nature of water and to carry out constructions to be able to store it, conduct it and use it for supply, irrigation, transport or moving machines.

Hydraulic projects also proliferated in Renaissance Spain. Madrid and the court promoted some of the most ambitious, which aimed to beautify the king's palaces, but also to improve the situation of the capital and the country. Although many did not go beyond dreams, dams, aqueducts, canals, piers and bridges were erected. Some of these constructions were at the forefront of contemporary Europe. In fact, they were drawn by engineers of diverse origins, born in the four cardinal points of the continent, but who moved among the main courts of the time and shared knowledge and aspirations.

From the popular technique to the imperial technique. The cases of Francisco Lobato, Pedro Juan de Lastanosa and Jerónimo de Ayanz

During the reign of the Habsburgs, talented people from Europe came to court to put their knowledge at the service of the kings. The moment of greatest splendor took place during the reign of Felipe II, who was surrounded by great technicians. Among these, Pedro Juan de Lastanosa stood out, who did excellent technical work, and, among his notable achievements, stands out the probable authorship of the most important hydraulics treatise of the time: The twenty-one books of ingenuity and machines. And also Jerónimo de Ayanz, author of more than fifty inventions, patented in 1603 and 1606, which anticipated those that would be current in the Industrial Revolution two centuries later.

But not only were there exceptional engineers at court, there were also them in the towns and villages developing innovative mills, such as Francisco Lobato, a versatile inventor who wrote a manuscript that allows us to discover the high level of popular Spanish technique.

The wonders of Juan de Espina and the legacy of Leonardo

The figure of Juan de Espina

Thanks to the testimony of the Florentine painter Vicente Carducho, we have news of the presence in Madrid in 1620 of two codices by Leonardo da Vinci. Carducho mentions having seen them at Juan de Espina Velasco's house. Although born in Madrid and a prominent courtier, the Espina family estate was located in Ampuero, and included mills and ironworks.

Juan de Espina managed to form a magnificent cabinet of wonders in his Madrid residence. His gallery coexisted with collections of natural objects (nature), instruments and decorative and exotic elements (artificial). In the library, Leonardo's two codices stood out. He bequeathed them to Felipe IV, which has allowed a part of Leonardo's work in Spain to be preserved to this day.

Espina was also known for its spectacular parties, which were sometimes attended by the best of the court. In them, devices, automatons, set design tricks and special effects caused astonishment. All this gave him a fame as a sorcerer, to which the literature of the time contributed. Comedies about him continued to be published for years, until the historical figure was overshadowed by the character.

Leonardo's artistic legacy

The valuation of Leonardo's work also evolved over the years. His worth as an artist surpassed the rest of his talents and his manuscripts became an object of collection and not study. The fact that these were never published prevented further dissemination of their knowledge. Only his thoughts and annotations on painting were compiled at his death by Francesco Melzi, forming what is known as painting treatment by Leonardo da Vinci. This allowed the dissemination of his studies on light and shadows, movement, proportions and physiognomy, the theory of perspective based on the use of color and his observations on the landscape. Studies and theories first edited in 1651 by Raphael du Fresne in Paris. The first Spanish edition appeared in 1784.

Proof of Leonardo's influence and inspiration on other artists are the drawings that have been selected for this room.

Image gallery

Catalogue

The catalog of Ingenuity at the service of power. The codices of Leonardo da Vinci in the court of the HabsburgsIt can be purchased at the exhibition itself, and at the Institutional Library of the Official Gazette of the Community of Madrid, where the general fund is sold, or in the main shopping centers.

Institutional Library of the Official Gazette of the Community of Madrid

Official Bulletin of the Community of Madrid

Official Publications Service

Fortuny Street, 51

28010 Madrid

Phones: 91 702 76 26; 91 702 76 21; 91 702 76 18

ISBN: M-31728-2020

Price: 20€